1905 Saint Petersburg, 1920 Dublin, and 1969 Istanbul: These are a few examples of bloodstained blots in the modern history provoked by social and political conflicts and resulted in civil injuries and deaths in often notable urban places of the world. Called according to the day of occurrence, the “Bloody Sunday” still keep its place in the historical memory of that states.

Turkey´s Bloody Sunday took place in 16th February 1969 at the heart of Istanbul. At eleven o clock ten thousands of left-wing students supported by labor unions and the labor party started gathering in Beyazıt in order to protest against the dropping anchor of the American Sixth Fleet at the Bosporus. The route of demonstration began at the Beyazıt Square, went over Karaköy, Tophane and Gümüşsuyu where they paid tribute to death of the student Vedat Demircioğlu at the Istanbul Technical University. Meanwhile right-wing students met at the Dolmabahçe Mosque for the suppression of the leftist protest and prayed before they moved on. The police, the official representative of the state, was already waiting at Taksim to both wings. Around four pm, finally, the clash occurred at the Taksim Square and turned the streets into a battlefield. Batons and knives were pulled. Molotov cocktails hurtled through the air. The exclamation against imperialism collided with the shouts of takbir and jihad. The call for independence crashed into patriotism. The outcome of this day, plunged in intolerance and violence, was the death of two leftist people and numerous injured. [1] [2]

This Sunday can be seen as a turning point in the student movements of the 60s`Turkey. In order to understand this event it is important to look at the political and social atmosphere of these complex and troubled years started with the first military coup in 1960 and ended with the Military Memorandum of 1971.

Besides the elimination of the old government the Coup of 1960 initiated the liberal Constitution of 1961. The enhancement of civil rights set in motion political latitude and diversity on Turkish streets. Student organizations, new parties and labor unions found fertile ground for flourishing. The government was quickly yielded to civil politicians after elections [3][4] but the Grand National Assembly was always overshadowed by the military which appeared as the protector of Atatürk´s ideology. Political instability was inevitable.

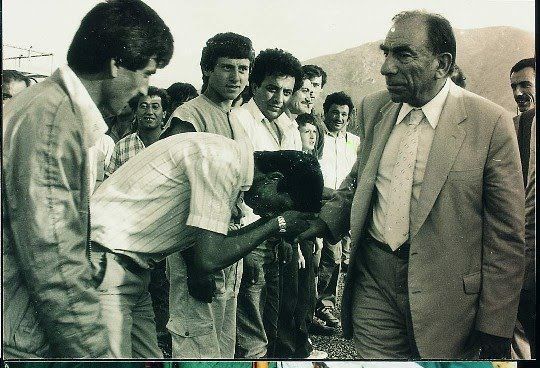

Another aspect of this period was the Cold War and Turkey´s international politics. On the one hand, the Turkish government was aside the American politics due to its financial dependence to the United States and its membership to NATO. On the other hand, anti-Americanism was steadily increasing among the young population like everywhere in the world as a reaction to American imperialist politics and cruelty in the Vietnam War. 1964 after a controversy between the American and the Turkish government over Cyprus, first large protests against the United States took place. [5] The protesting students shifted more and more to the socialist ideology represented mainly by the Workers Party of Turkey. In contrast the right wing grasped obdurately on its nationalism and the traditional values of the society. 1965 Alparslan Türkeş, one of the leading heads of the Coup of 1960, joined a nationalist party and introduced the “Doctrine of Nine Lights“ [6]. His “Grey Wolves” would become one of the decisive figures of the following years in the republic.

This worldwide tension exploded in universities in 1968. The Cold War disunited not only the world in two parties but also societies: American attitude against Russian ideologies.

The starting point of the protests in Turkey was Ankara. As the Workers Party was expulsed from the parliament, the leftist movement fluxed to the streets followed by their counterparts the right wing students. [7] The anchoring of the Sixth Fleet at the Bosporus, which became the symbol of American influence over Turkey, added fuel in the fire. During the events following this incident the first victim of student movements fell. By a police raid in the Istanbul Technical University Vedat Demircioğlu fell out of the dormitory window. [8] The consequence was a further radicalization in universities and on streets. Alparslan Türkeş´s party organized military camps for training the “Grey Wolves”. Some students of the leftist movement armed itself in Palestine camps apprehending that the revolution could not be applied with democratic means. [9] As the Bloody Sunday arrived both groups had been already accepted radical steps for defending their aims.

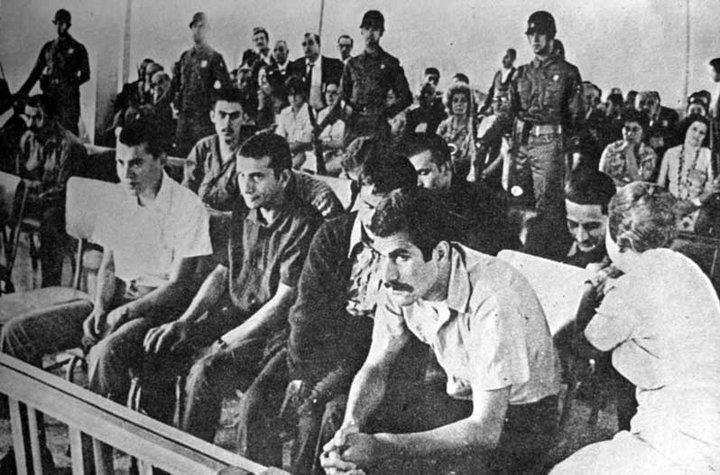

Additional to this left and right dichotomy, the following years of Turkey was embossed with crises in foreign policies, financial crisis, uprisings of workers and a week government who tried to suppress the quarrels on streets with the aid of armed forces. Finally in 1971, the army came out on top again. Martial law was declared. Parties, student organizations were banned and universities were closed. Prisons were full of students and leftist intellectuals. The left-wing movement of the republic was rigorously devitalized. Turkey started a new era over the dead bodies of the three leftist students Deniz Gezmiş, Yusuf Aslan and Hüseyin İnan, who were punished with the death penalty. However, Military Memorandum of 1971 could not terminate the riots and the Taksim Square should witness further violence and bloodshed in the following years. [10]

[1] Mahir Deniz Ibo, Anlatılan Senin Hikayendir, Bir Gün Gazetesi, Kalkedon Yayınları, Istanbul 2009

[2] bianet.org/biamag/siyaset/112604-40-yil-once-kanli-pazar-da-ne-old

[3] Mehmet Ali Birand. Can Dündar, Bülent Çaplı, Demirkırat: Bir Demokrasinin Doğuşu, TRT, 1991 Türkiye, part: 10

[4] Mehmet Ali Birand, Can Dündar, Bülent Çaplı , 12 Mart-İhtilalin Pençesinde Demokrasi, 1991 Türkiye, part:1

[5] Mehmet Ali Birand, Can Dündar, Bülent Çaplı , 12 Mart-İhtilalin Pençesinde Demokrasi, 1991 Türkiye, part: 5

[6] Prof. J.M. Landau, Türkiye´de Sağ ve Sol Akımlar, Turhan Kitabevi, Ankara 1979, p: 296-298

[7] Mehmet Ali Birand, Can Dündar, Bülent Çaplı , 12 Mart-İhtilalin Pençesinde Demokrasi, 1991 Türkiye, part: 7

[8] Aydın Çubukcu, Bizim `68, Evrensel Basın Yayın, Istanbul, 2008,p: 77-78

[9] Mehmet Ali Birand, Can Dündar, Bülent Çaplı , 12 Mart-İhtilalin Pençesinde Demokrasi, 1991 Türkiye, part:7

[10] Mehmet Ali Birand, Can Dündar, Bülent Çaplı , 12 Mart-İhtilalin Pençesinde Demokrasi, 1991 Türkiye, part:1