During the Ottoman reign, numerous Bektashi lodges spread across Istanbul. Some of them or their remains have survived to date such as; the Şahkulu Sultan Dergahı in Merdivenköy and the Emin Baba Tekkesi in Edirnekapı[1]. However, the few remnant traces do not effectively portray the position of the Bektashi order in the Ottoman Empire.

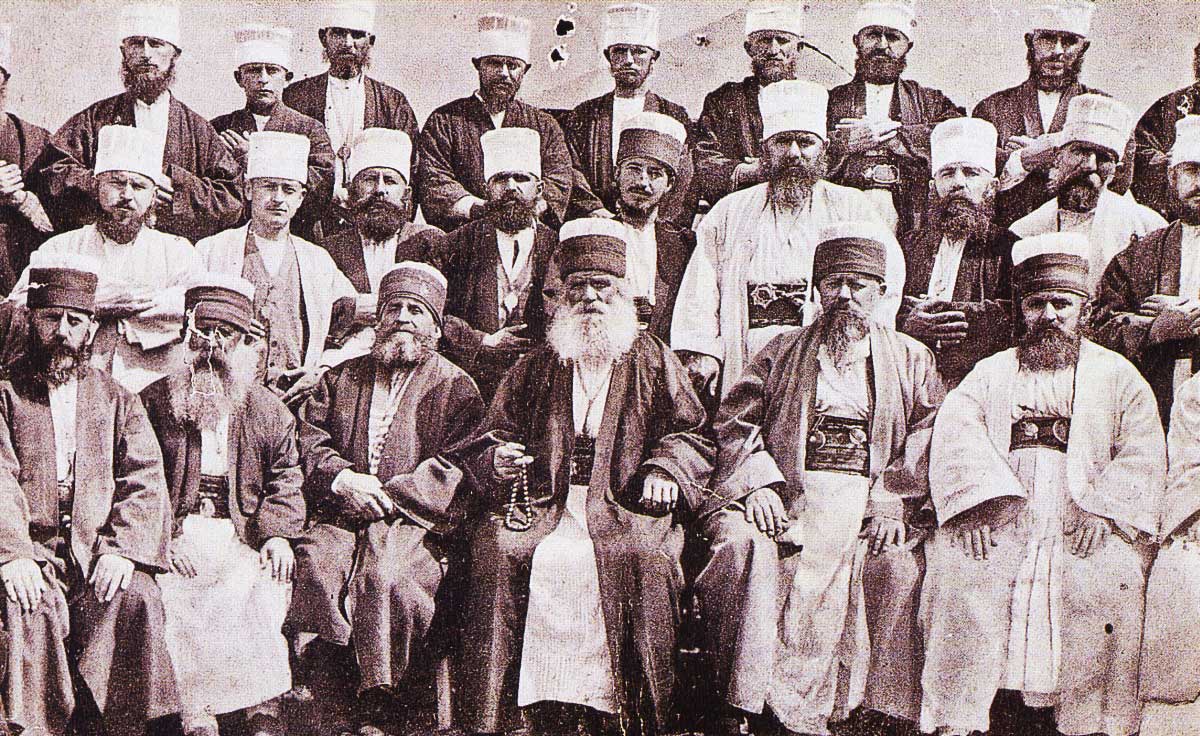

The foundation of the order by Hacı Bektaş Veli near Kırşehir dates back to the 13th century[2]. For a period of time, the Order stayed as a spiritual movement without any sturdy tendencies to concretise it. In the 16th Century, Balim Sultan who seemed to develop connections with the ruling elite institutionalised the order henceforth establishing a hierarchical system. The system introduced consisted of the aşık, the dervish, the baba and the dedebaba at the top. At the bottom is aşık who despite having access to the order are not still privileged to the Bektashi’s secrets. Above the aşık are the dervish who are officially initiated into the Order. In between the dervish and the dedebaba is the baba who not only serves as the head of a lodge, but also as a teacher to the aşıks and the dervishes. On top is the dedebaba who is the spiritual leader of all the lodges[3]. The essence of a dervish is to journey through the four doors leading to the all-embracing Divine Truth while being accompanied by a spiritual guide. Despite being open to everyone, it is only after attaining dervish status that one gets to know the secrets of Bektashism. This openness and flexibility often times resulted in harsh criticism against Orthodox Islam[4].

Bedri Noyan, the Dedebaba of the Turkish Order until 1997 breaks down the spiritual fundamentals of Bektashism in the following words;

- Sufism is a movement which emerged as a reaction to the strict sharia laws of Orthodox Islam. By softening the rules and enlarging its meaning, the faith is saved from external influence by evoking the true meaning of the Qur’an thus enriching its content and scope. Furthermore, instead of looking at the plural meaning, it focuses on the unity or singularity of a meaning. The spirit is also gradually cleaned through maturity[5].

- Its existence is unique, it does not multiply, reduce, change or divide itself. It does not have shape, appearance or limit. Everything is bound to it whilst it is bound to none[6]. For the Bektashists, material and the universe is just another face of God[7], which means that every human is a reflection of God and an appearance of the Divine Truth[8].

- Bektashism uses love as a human ideal for establishing a universal bond. The aim of which is to connect the whole humanity within a faith by viewing love as the one truth in the universe[9].

Christian, Shamanistic and Shiite elements can be found in Bektashi practices. For example, the adding of women into the rites or the legend about Hacı Bektaş’s transformation into a dove has shamanistic roots[10]. Ali´s significance in the order is the most outstanding element taken from the Shiite doctrine. Perceived as part of a trinity with God and Mohammed, in dualism with Mohammed or even considered to be superior to Mohammed, Ali holds an eminent position[11]. In relating Christianity and Bektashism, the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste are recognised as ‘Kirklar’ by the dervishes[12].

Owing to the close connection between the dervishes and the military force especially the Janissaries, the Bektashi Order spread as the Ottoman Empire expanded. Bektashists were religious leaders of the Ottoman infantry which was a key factor when it came to processing child levy, Islamification and becoming a Janissary[13]. The Order through the Janissaries were important parties of the Ottoman politics. At their peak, two sultans were deposed resulting into the so called Vaka-I Hayriye. It was in 1826 under the reign of Mahmud II that the Janissaries were abolished and so was the Bektashi Order. About 100 years later, the Bektashi were threatened with abolition due to the introduction of laicism in the newly declared Turkish Republic. Despite an official ban today, Sufism centres are still existing and tolerated by the Turkish state[14].