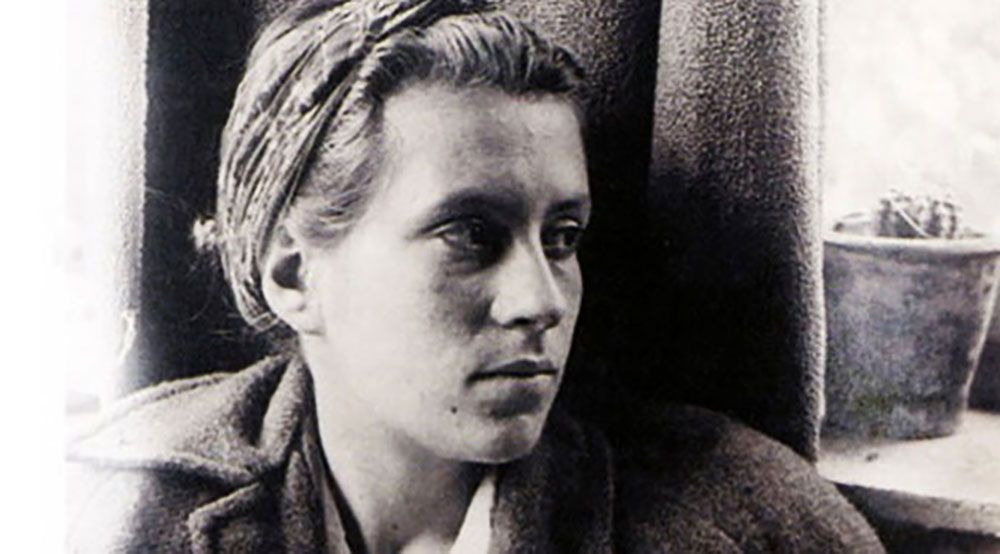

The black is all-embracing. Only the light of the projector casts flags over the face of a person who is squinting into the darkness: the Turkish, the German, the Cypriot and the Russian flag. There is nothing else to see; you just hear the movements of the bulky camera. Paul-Ruben is standing behind the camera. “Don’t move”, he instructs the person in front of the camera while he captures each portrait. And this is a serious order because he uses a large format camera. This is the camera whose body looks like an accordion and which you may know from old movies. The photography student vanishes under the dark cloth and captures items with his camera. Full silence. No shrug, no blink is allowed. And just the poor light of the projector, which illuminates the people and leaves them the marks of the flag, serves as a source of light.

Most of the time there are multiple flags of different countries because Paul-Ruben Mundthal’s photo project “RADEBRECHT: A portrait series about in-betweenness” deals with nationality and how it effects the understanding for the own identity. How does it feel, if you need visa for the entry of the country where you grew up, if you are a stranger on paper, the not-belonging-person, in the country that you call homeland, if you have to decide between two passports for one, symbolising two countries´ traditions, culture and habits that you unite in one body?

“It feels like an amputation, like you have to decide for your left or right leg”, says Zeynep. She is one of the people that Paul-Ruben asked to stand in front of the objective. Zeynep grew up in Germany, her parents come from Turkey. The crescent of the Turkish flag and the three stripes of the German flag are shining on her face, as Paul-Ruben turns the objective of the camera to her.

Mehmet, who also gives his story and face to this project, could not decide. His parents moved from Bulgaria to Turkey in the 90s. At that time, he explains, Turkey and Bulgaria negotiated over the Bulgarian Turks, the minority to which his family belongs. They could resettle to Turkey without any great visa regulations and because they hoped for jobs and better living conditions, they packed their bags and moved. Then Mehmet became naturalised. Now he has the Turkish passport. He would prefer the Bulgarian one, also because of the reason, that the adoption of his name from the Cyrillic alphabet was a little bit sloppy. Mehmet (Мехмет) have become Mexmet. A real identity-commingling.

And, where are you from?

“The nationality, which you carry in your pocket, does not often correlate with your own feelings”, says Paul-Ruben. As he came as an Erasmus student to Turkey, the standard question of each first conversation was: Where are you from? For Paul-Ruben it is actually a question that he could easily answer. Grew up in Neubrandenburg, studied in Weimar, lives in Erfurt. Germany. However, the more people he met whose stories were more unusual, the more he realised that the system which is created by states with expressions like “citizenship” and “nationality”, does not do the global world in which we live justice.

Paul-Ruben is currently studying at Mimar Sinan University for a year. There, during the class “Gender and Identity” he came up with the idea of his portrait series. He wanted to look into the question of how much identity and nationality is linked with each other. During the research he realised how extensive this issue was and that it posed further questions: Where do you feel at home? What does this feeling define? And also, what does it mean to carry a passport of the country x,y,z?

The master student met people, who carried with them the most absurd stories. In the end twelve portraits and twelve interviews became the result of Paul-Ruben’s search for answers. Answers to the question of what the piece of land where we were born, grew up and lived really mean for us, and what it means to see this belonging confirmed on a piece of paper.

Seçkin was born in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. His father insisted that he got the Turkish passport instead of the Turkish-Cypriot one. This passport is called “fantasy passport” because the UN does not recognise the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus as a sovereign state. That means that the entry with this passport is just possible in few countries. Seçkin now lives with the Turkish passport in Istanbul. If he wants to go home for a longer period, he has to apply for a visa. A strange feeling.

A further person from Paul-Rubens portraits series, Sevinç, needs a residence permit for the allowance to stay in the country where she was born and grew up. Her parents come from Azerbaijan and Russia. She has the Azerbaijani passport. Every two years she must go to the public authorities and apply again in order to live on in Turkey, in Istanbul, in her homeland. It was the decision of her parents. Now Sevinç does not want change this anymore. Istanbul is her hometown. And everyone here comes from somewhere else. Besides Sevinç is enrolled in the university as a foreign student and would lose her university place, if she would become a Turk.

The German Passport as a Gold MasterCard

If you have the choice to choose between two citizenships, your decision often depends upon which passport has the better features: Which citizenship gives you greater opportunities, with which one do you live cheaper, which one offers more freedom? And at the same time you realise how random nationality is. It seems to be like lottery. Depending on the regulations of states it is just a question of your birth place or the nationality of the parents whether you are Turkish, Russian or German. Over the course of the project Paul-Ruben has figured out quickly that the German citizenship is like a jackpot. Offering homelike security and almost boundless freedom to travel, the German Passport is almost a MasterCard Gold which opens doors and opportunities in minute cycle. And this passport is just bestowed on him, a passport that was neither his decision nor his achievement. And behind this passport there is a concept that shows how the world is divided, how value is assigned and how a particular order is created.

Paul-Ruben has used the flags as symbols of nationality. He draped them through photoshopping and printed them on projection sheets, which he fixed on the projector. “Little by little these sheets have become scratched”, he tells. “This was, of course, not my aim but the effect was visually fascinating and provided much more symbolically.” The flags merged with each other and dissolved.

And in the end this is the message that Paul-Ruben wants to transmit. Flags, nationalities, citizenships, these are constructs, which do not play any role once people want meet truly. He thinks: “All that counts are what people keep in their heart, not what is on paper.”

Text: Marie Hartlieb Translation: Serap Güngör

In Robert-Houdini’s memoirs, the author mentions Bosco as his rival and he describes him as a magician who conjured in bizarre costumes on a stage crowded with tools and decorated with skulls and candelabras, declaring that the tasteful style chosen set his performances apart from other conjurers.

In Robert-Houdini’s memoirs, the author mentions Bosco as his rival and he describes him as a magician who conjured in bizarre costumes on a stage crowded with tools and decorated with skulls and candelabras, declaring that the tasteful style chosen set his performances apart from other conjurers. After that Bosco grabbed his sword, he raised it in the air and he took some time with this gesture. Then, he lowered the sword and asked the Sultan a preparation period of three weeks during which he would have to collect certain herbs that needed to be used during the number. So, the Sultan granted an extension, but after just eight days Bosco managed to escape to Russia.

After that Bosco grabbed his sword, he raised it in the air and he took some time with this gesture. Then, he lowered the sword and asked the Sultan a preparation period of three weeks during which he would have to collect certain herbs that needed to be used during the number. So, the Sultan granted an extension, but after just eight days Bosco managed to escape to Russia.