On a hot summer day in Finike, best known for its oranges, the symbol of the town, my Turkish friend and I were walking down the aisle of farmers markets where the bright colours of fresh food mingled with their delicious scents creating a fairy-tale like atmosphere that completely absorbed us. For a moment a stallholder, who was an old and cheerful man, stopped us and invited us for Turkish tea. He said that our hippie-like look had attracted his attention. In the middle of the conversation that had begun with this stallholder, I began to look at what he was selling, seeing this, the stallholder began to talk about his goods in Turkish. I was waiting for the translation of this by my Turkish friend, but they themselves were preoccupied with looking at me and laughing. In the end everything became clear; what he sold was Harnup Pekmezi and what the old man was telling my friend was what the reputation of this product was known for – heightening arousal and sexual drive.

Dolmas: A Turkish Staple

If you are lucky enough to find yourself invited to a home cooked Turkish dinner, you will find among the many mezes on offer, stuffed vine leaves or Dolmas. But don’t wait too long while perusing the dishes on offer, or you may find your fellow dinner guests have eaten them all. This dinner party disaster has happened to me on several occasions and I thought it was time to address the issue, and consider the humble Dolma for the diverse and delicious dish it is.

Kokoreç Ko Ko Ko Ko!

“KOKOREÇ! KO KO KO KO!” I faintly notice the praising screams as I push myself through a narrow yet crowded lane in Beşiktaş. Little did I know at this point that what the proud food shop owners were selling was one of the most popular and infamous national dishes that the Turkish cuisine offers. I would have my chance though.

Ibrahim Muteferrika’s Statue in Istanbul

Visiting Istanbul could only be incomplete without a relaxing search for books; old, new books, nothing compares with browsing trough open air book shops. And one of the most suitable places is in Beyazit Square, next to the Grand Bazaar. Book lovers and bazar hunters, this is your place, you cand find anything. The book bazar, between Beyazit Mosque and Grand Bazzar is placed on the actual site of an historical landmark, where the Chartoprateia – a Byzantine book and paper market existed. During the Ottoman era, the site became a center for printing and literary trade, drawing many intellectuals in this area. [1]

A City Which Raised Me Up

I will never forget the first time my foot touched a magical city Istanbul which as I learned in the following years taught me a lot and even raised me up.

Four years ago a girl which was only 18 years old was sitting in a bus which was bringing her from Antalya to Istanbul. She just graduated from school and instead of enroll to university, she decided come to live in Turkey. It was almost a midnight when she first time saw the city which became her real home. As a girl which was born in a very small town with population of 10.000 people she was looking through the bus window and was trying to figure it out where the city is starting and where finishing out. She couldn’t understand the size of it and she was so surprise when she found out there was even few bus stops and she don’t know which one she needs to get off.

Holy Nights and Turkish Bagels

In order to explore a society blended with different cultures, it is necessary to examine the Islamic point of view as the majority’s religion, which influences traditions. There are five main holy nights in Islam – Mawlid, Ragaib, Isra and Mi’raj, Night of Bara’at, and Laylat al-Qadr. Those holy nights on the Islamic calendar are called “Kandil” (candle) in Turkey since candles are lit on the minarets of the mosques to announce these holy nights to the public with one of the Ottoman Sultans, Selim II’s order during 16th century. In addition, since the Islamic calendar is calculated with the revolution of the moon around the earth, the dates of the holy nights change every year.

In Turkish culture, holy nights have a unique purpose compared to other Muslim societies. They include calling close relatives and friends to celebrate their holy night, beside praying for being forgiven and reading the Quran with their beads. Furthermore, most Muslims cook halva, holy night bagel or they buy at least seven packets of pasta, granulated sugar, rice, or seven loafs of bread to share with their neighbors. Let’s take a closer look at those holy nights and their importance for Muslims.

Mawlid: the word ”Mawlid” means the birth time in Arabic; therefore, Mawlid is the day for celebration of the Prophet Mohammad’s (Muslim’s prophet) birth. Until it had been celebrated approximately 350 years in Egypt by the Fatımid Empire, there was no such kind of celebration in Islamic culture. The date of the holiday changes depending on denominational differences, so the Sunni people celebrate on the 12th night of the Rabi’ al-awwal Month while Shiites celebrate on the 17th night of the Rabi’ al-awwal Month, according to the Islamic calendar.

Ragaib: “Ragaib” means to incline in Arabic and actually it has not been given a place, but Muslims have started to celebrate it over the years so it has become one of the holy nights. They believe that if they pray enough that night, they can go to heaven and their sins are forgiven. It is celebrated on the first Thursday of Rajab Month according to the Islamic calendar.

Isra and Mi’raj: The word “Mi’raj” means the stairs and ascension in Arabic, and Muslims believe that Mohammad traveled to heaven to have a conversation upon God’s request. The trip that is expressed in Surat al-Isra and Surat an-Najm has two parts; first he traveled from Masjid al-Haram to Al-Aqsa Mosque (the first kibla* for Muslims in Jerusalem) then he traveled to heaven to see God. This night is the symbol of redemption and circumcision, five times salath has become necessary for Muslims. It is celebrated on the 27th of Rajab Month, according to the Islamic calendar. As mentioned previously, Muslims pray for forgiveness and good wishes, and some of them fast that day. Some believe that wine, honey and milk are brought for him and he chooses milk among them. Thus, in Anatolia most people drink milk or prepare desserts with milk and share it with their neighbors. Also, it is called “Milk Night” in Konya for the same reason.

Night of Bara’at: The word “Bara’at” in Arabic means the night of innocence and freedom. According to Muslim belief, God freed his sinful servants who were destined for Hell. A person’s life in the coming year, his sustenance, and whether or not they will have the opportunity to perform Hajj (pilgrimage) shall be decided on this night. The names of the souls of all those who are born and of all those who are to depart from this world are determined. One’s actions are done and then sustenance is sent down. It is celebrated on the middle night of the Sha’ban Month, according to the Islamic calendar. Muslims pray more than usual during that night to change their destiny

Laylat al-Qadr: The meaning of the day is the night of decree, of value or destiny. According to Islamic belief, the Quran was revealed to Mohammad for the first time. The Quran was completed verse by verse in 23 years of revelation to Mohammad by Gabriel, the angel. It is one of the odd nights of the last ten days of Ramadan and is one of the most important and valuable days for Muslims. They believe that the blessings and mercy of God are abundant, sins are forgiven, prayers are accepted and the annual decree is revealed to the angels who also descend to earth on this night. Most Turkish Muslims complete reading the Quran (reading all of the pages of the Quran is called “hatim” in Turkish) by this night each year and pray that their sins are forgiven.

After all this religious information, I would like you to explore these holy nights from a different perspective – the food perspective! On all the holy nights, you can see holy night bagel (little ring-shaped dough covered with sesame seeds) in Patisseries for just holy night days. Some Turks make it in their home and share it with their neighbors. Here is the recipe for holy night bagel:

Ingredients:

*125 gr butter

*2 eggs

*1 tea glass of oil

*2 table spoon vinegar

*1 table spoon mahaleb

*1 table spoon granulated sugar

*1 dessert spoon salt

*1 packet baking powder

* 3-4 glasses of flour

Preparation: leave the eggs and butter at room temperature and separate the egg whites and yolk. Put the flour in a deep bowl and make a hole in the middle of it. Add the egg yolk, butter and other ingredients. Then knead the dough and add flour little by little until it become soft enough. Take a piece of dough the size of a walnut and roll it into the shape of a ring. Put a greaseproof paper on the tray and put down the holy night bagels you prepared. Then apply the egg whites that you separated before with the help of a brush. Lastly, sprinkle sesame seeds and put them in the oven at a temperature of 190 degrees C. Bake them until they are brown. Your holy night bagels are then ready to eat and share! Happy holy nights!

Ottoman Sherbet

When you think of Ottoman cuisine, images of exotic herbs, roaring fires and boiling pots might come to mind. And who could forget rows and rows of Lokum and Baklava being prepared. While the popularity of many staples of Ottoman cuisine remain as popular today as they did 300 years ago (you only have to walk twenty metres down Istiklal to see the demand for a sweet slice of baklava hadn’t changed much), some treasures enjoyed by the Sultans have been almost forgotten to time. Ottoman Sherbet, from the Arabic sharba, meaning “a drink” is one such example. Once as popular in Turkey and parts of the Middle East such as Iran and Afghanistan as cola is today, this sweet drink, prepared using fruit and flower petals, has a long and rich history. Like many Ottoman dishes, Sherbet appears in quite a few anecdotes. When an Ottoman vizer had found he had displeased his sultan, he was served a glass of sherbet by one of the Sultan’s Bostanbasi, an elite squad of gardener-executioners. If the sherbet was white, he would live, if it was red, he would know he was a condemned man.

1896 Occupation of the Ottoman Bank

The occupation of the Ottoman Bank (Bank-ı Osmanî-i Şahane) is regarded as the first recorded act of urban terrorism and was one of the most important elements that sparked the chain of events now known as the ‘Armenian Question’. Among all the Armenian attempts to catch attention the takeover of the bank was a true catalyst as it involved British, French and Ottoman capital. The Armenian revolutionaries aimed to create chaos in the Ottoman capital in a hope that the riots would be reported in the international press. In this way they could demand attention for the “Armenaian Question”. Furthermore, they expected the British and French armada to approach Constantinople for military intervention. The operation was masterminded by the Armenian Dashnak Party as they saw such an action as a chance to move ahead of the Armenian Hunchak Party which was responsible for almost all the other actions at that time.

A Musical Bridge from Italy to Turkey: Giuseppe Donizetti

“(…) We heard Rossini’s music, executed in a manner very creditable to Professor Signor Donizetti. (…) I was surprised (…) on finding that they were the royal pages, thus instructed for the Sultan’s amusement. Their aptitude in learning, which Donizetti informed me would have been remarkable even in Italy, showed that the Turks are naturally musical.” (Sir Adolphus Slade, British naval officer, late 1820s)

Continue reading “A Musical Bridge from Italy to Turkey: Giuseppe Donizetti”

Life in Çukurcuma, Land of Antiques

Welcome to Çukurcuma Street, the land of antique shops. Maybe some of you know Cihangir quartier, since it’s included in most of the touristic guides. However, it has nothing to do with the breathtaking mosques of Sultanahmet or the frenetic rhythm of Istiklal Avenue. I will try to briefly describe this amazing corner of Istanbul and what I’ve been feeling since I moved here almost seven months ago.

Istanbul Hosts 18th Puppet Festival

The puppets take over Istanbul,

For the 18th time Istanbul is celebrating its International Puppet Festival, which started from October 13th and will continue for the next week until October 25th. The festival is organized by the Istanbul Karagöz Puppet Foundation and gathers different puppeteers from all over the world with the aim to bring out the child inside of you.

The First Turkish Cartoonist: Ali Fuad Bey

“English humour is hard to appreciate, though, unless you are trained to it. The English papers, in reporting my speeches, always put ‘laughter’ in the wrong place.” With this quote, famous English writer Mark Twain, expresses his scepticism towards English humour. Still, I believe that he was very happy when he witnessed the birth of comic magazines all over the world. I mean, he is Mark Twain, who is famous for writing satire, and the person who said: “humour is mankind’s greatest blessing”. Bang on! Who can deny what he says? The humour has always been an inseparable part of human culture. Even in antiquity there were professional joke books, and there was Democritus, who is known as the “laughing philosopher”. Artists of middle Ages or Renaissance were well acquainted with comic arts. Leonardo Da Vinci, Claude Monet, Agostino Carracci and Giovanni Bernini drew caricatures. Even Honore Daumier was in prison for a while due to his anti- monarchist caricatures. These caricatures reached their full potential after portrait-caricature was invented during the late 16th century. In spite of that, the beginning of caricature is marked by the cartoon-historians with the work of John Leech which was published in Punch magazine on 15 July 1843.

Starting from the mid-1800s the caricature magazines started to be published in the world and this trend evidently made its way to the Ottoman Empire. The first caricature was published in the Istanbul newspaper by Arif Arifaki in 1867, and the first Turkish humour magazine was “Diyojen” which was founded by Teodor Kasap in 1869. Despite publishing a few caricatures, “Diyojen” was truly a milestone in Turkish caricature history as it was an inspiration for everyone that followed. The development of the caricature in Turkey continued with the establishment of a number of humour magazines, and among them “Çaylak” magazine was most important as it was sort of a school for young talent artists of the period and moreover it was the first humour magazine published in the Ottoman Empire by a Turk.

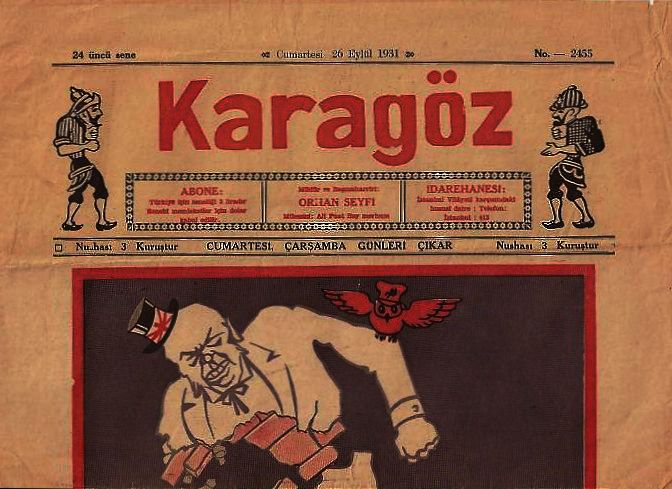

The time when the humour magazines mushroomed in Istanbul, Sultan Abdul Hamid II ascended the Ottoman throne with the promise of parliamentary government. Indeed, the sultan kept his word, however the 1st parliamentary period lasted only 93 days. Immediately afterward a despotic rule started to prevail which lasted more than 30 years until he was deposed in 1909 following the events related to 1908 Young Turk Revolution. During that time there was no way to print a humour magazine within the empire and consequently Turkish humour magazines transported to Europe, especially to France and Britain, where they continued to exist. Together with the declaration of the Second Constitutionalism in 1908, the censorship on humour magazines was abolished, and furthermore the press was granted limitless freedom. This gave green light to the artists who escaped to Europe. They returned back to their homes and established large numbers of humour magazines in Istanbul. Among all the papers that were established at that time “Karagoz”, which was founded by Ali Fuad Bey in 1908, was the longest lasting one.

Ali Fuad Bey, the founder of Karagoz newspaper, is regarded as the first Turkish caricaturist. Despite that there’s almost no information about his life, even in the works of Reşat Ekram Koçu, who is known for the famous Istanbul Encyclopedia, and in Sicil- Osmani, the Ottoman national biography. What we know about his life today comes from a few journalists and the memories of Ahmet Rasim, the famous Turkish writer and a close friend to Ali Fuad Bey.

Ali Fuad Bey starts his career as a journalist in a newspaper called “Basiret” in 1869, and later on he was the manager of Ottoman naval printing house. His first caricature was published in “Letaif-I Asar” newspaper in 1874. The following years he continued to publish his drawings in many important humouristic papers, of which“Caylak” was the most important. It was at “Caylak” where he spent his most fertile period and improved his skills a lot.. Çaylak magazine usually attacked and criticised Sultan Abdul Hamid II, especially during the Russo-Turkish War 1877-78. During the way Ali Fuad Bey fled to Europe, as did his colleagues, due to the sultan’s prohibition of humouristic magazines. He returned back to Istanbul following the deposition of Sultan Abdul Hamid II, and launched a new magazine called “Karagöz”, meaning black eye in Ottoman-Turkish, and referring to one of two lead characters of the traditional Ottoman shadow play called “Hacivat and Karagöz”. The reason why he chose Karagoz instead of Hacivat had meaning. The character Karagöz in this shadow play is best known for his sharp tongue and social commentary which even criticised the Ottoman sultan.

On 10 August 1908 the first issue of Karagöz was published with a slogan of “Illustrated amusement gazette, for now published on Mondays and Thursdays”. Ali Fuad Bey took on a task of illustrations meanwhile Mahmud Nedim was the author, writing the dialogues underneath the illustrations. The paper consisted of four pages, the first of which was left for the dialogues of Karagöz and Hacivat. The paper used very clear language in combination with the cartoon satire which helped everybody understand the political, social, economic and cultural events of the period of 1908-1918.

From the beginning of the Turkish Independence War Karagöz took sides on the Ankara government, the nationalists led by Mustafa Kemal. After the war resulted with the victory of the nationalists, Karagöz paper was taken as a vehicle to realise the nationalist ideal. During this period the new government practices were positively imposed upon the public. After one of the new practices of Turkish government, replacing the Arabic script with the Latin alphabet in 1928, Karagöz paper lost many of its readers, and it was sold to the Republican Peoples Party. From that point on, it continued to be published under the editorship of Sedat Simavi, who is a legendary figure in Turkish media history and best known for the Hürriyet newspaper. After Democratic Party won the 1950 elections, which ended the one party period in Turkey, Karagöz lost its effectiveness completely, and finally the last issue of the paper was published in 1955.

What really makes Karagöz very special is that among all the papers which were established within the same period Ali Fuad Bey’s Karagöz was the only one which witnessed the Second Constitutionalism period, the World War I, the Turkish Independence War, the foundation of the Turkish Republic, one party period as well as the first five years of the real democracy in Turkey. During its publication life of 47 years, there were more than 4000 issues that were published. In this way this paper is the first degree historical source together with a chronological order!!!

By the way don’t get confused! Ali Fuad Bey had no chance to witness all the events that Karagoz published about as an eye-witness. On the other hand his date of death is as polemical as his date of birth. According to Orhan Koloğlu Ali Fuad Bey died during the 1920s on the other hand many number of researcher agreed that he died on 27 August of 1919.

Tahini Time: A Sesame Spread You Don’t Want To Miss

I thought my first encounter with tahini was when I stumbled into a cafe in Cihangir, hungry from running 10km in the 36th Istanbul Marathon, ready to dive into the breakfast spreads and breads before me. At that moment, the tahini dip—fragrant, toasty, creamy tahini—was so special and novel, that I wondered how I could possibly get more of it. But it seems like I already had. And, guess what, you probably have tasted this sesame seed spread before as well.

Continue reading “Tahini Time: A Sesame Spread You Don’t Want To Miss”

Wild Herbs of Aegean

In the Aegean region of Turkey, one cannot think of any dinner other than a meal prepared with vegetables or herbs. Having moderate climate conditions, the Aegean region provides available conditions for growing vegetables and herbs. Especially in spring, countrywomen go into the woods to collect herbs for cooking or selling them at bazaars. Local people believe that, as Cretans said, each herb which goats eat is edible; therefore, there are many types of herbs that Aegean women collect and cook. Those herbs can preferably be fried or boiled, but most of the time they are accompanied with yoghurt. As a warning, those herbs should also be consumed in certain proportions in one day.

Queen of the Ramadan Desserts: Güllaç

There is a strange quiet atmosphere on the streets of Istanbul, the night is about to fall, and a mystical air is lingering over the city. Very few of people are wandering around, almost all the shops are closed, and at that time the muezzin starts to call for prayer, but even that sounds different. Istanbul, the city of 15 million, seems like a ghost town from a horror movie. What happened to this chaotic and hectic city? Where are all the people? Am I dreaming? No. No. Everything is real. Nothing serious, just Ramadan!

A Revolutionist in Istanbul: Leon Trotksy

On February 1929 Leon Trotsky entered Istanbul per ship accompanied by his wife Natalia Sedova and his son Lev Sedov. When he arrived he was a man who had experienced a gradual downfall. He started as one of the most powerful man in Russia, the co-leader of the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the head of the Red Army, but soon became public enemy number one of the Soviet Union in Joseph Stalin´s eyes. Exiled from his homeland the young Turkish Republic was the only country which accepted Trotsky within its borders.

Continue reading “A Revolutionist in Istanbul: Leon Trotksy”

History of Beyoğlu: From Pera to Beyoğlu

Time changes everything we see, touch and feel… This is the constant rule of life and it holds for everything. Style changes, people change, attitudes change, words change and tastes change… Beyond any shadow of a doubt, the Ottoman Empire evolved through time in the same way. So did Constantinople, the capital of the glorious empire, and its European neighbourhood, Pera…

Those who have read “The Longest Century of the Empire” by Ilber Ortaylı, the most popular modern Turkish historian, would know that the 19th century is literally a milestone century for the Ottomans. The 19th century witnessed astounding historical events such as revolutions, financial developments, new ideologies, and other inventions, and all these events hastened the momentum of change in the world. Ottomans couldn’t adapt themselves to this new change therefore the rise of a new aggressive European imperialist movement brought the Turks to their knees. The Ottoman Empire slipped into a period of stagnation and a state of degradation, which prompted Russia’s Nicholas I to nickname the empire “the sick man of Europe”. This galvanised the Ottoman politicians into action, reforming their government and society by engaging in Westernisation. It has been said that Constantinople formed the centre of all the head-spinning changes, but realistically it was Pera. A European neighbourhood in a Muslim city, Pera, was the best place to start.

According to Ottoman documents, Pera was the area across the old peninsula and beyond the Galata neigbourhood. Today, when we say Beyoğlu, we usually think of the area between Taksim square and Karaköy. However, in the past, there was a sharp distinction between Galata and Pera. Galata comprised the area between the Galata Tower and the Karaköy coast. It was a port in the 13th century, used by Genoese tradesmen, and one of the most important international maritime outposts in the region. Pera did not flourish as fruitfully as Galata, because there was neither enough water nor any means of communication with the other side of the Golden Horn, which was the heart of the city at that time. In a way, Pera was Galata’s summer place, overflowing with vineyards and orchards, and scarcely populated by non-Muslims, save for a few Muslims living around the dervish lodge of the Mevlevi order.

To discover the answer of how Beyoglu evolved as a western neighborhood right in the middle of the Muslim city, we should look back to the 16th century when François I of France, who was the first monarch to establish diplomatic relations with the Ottoman sultans, built the first foreign embassy in Pera in 1581. With that precedent, installing embassies in Pera thus became the order of the day. The relocation of all embassies was completed by the 19th century. This became the most important factor in the development of the area, which also saw the area attaining a European atmosphere.

One serious problem that inhibited population growth in Pera was the lack of potable water. The solution finally arrived in 1732, in the construction of the distribution chamber. This chamber, or “maksem”, distributed water from the Bahçeköy Aqueduct around 20 km away, to fountains in Galata and Pera. When water flowed in abundance, so did the crowds of families and workers.

The construction of the Galata Bridge was another important event that played an essential role in the development of Pera. It was first built in 1845 with the name of “Cisr-i Cedid” and replaced with a wooden design in 1863. The bridge linked the production centre (old city) with the heart of imports and exports (Galata). This connectivity created an economic boom dominating the area between Sultanahmet and Galata, which soon became a hub of activity. This new atmosphere overcrowded the small port of Galata, so it needed to expand towards the open areas of Şişhane and Istiklal Avenue of today’s Taksim. New quarters were created and old ones were reshaped and repopulated by wealthy families.

The treaty of Balta Limanı, the Anglo-Ottoman commercial treaty, and the Tanzimat reform, the Reorderings, were very important events that should definitely be mentioned. The commercial treaty opened up the Ottoman Empire to free trade, and was then dominated by Western powers, which made the Ottoman Empire integrate into the global capitalist system. In addition, the rule of equality of all citizens under law was consolidated in the Tanzimat, a political reform program. These new policies bolstered optimism within the empire and consequently, Constantinople became a magnet attracting European merchants and Western travellers. Nearly 100,000 new foreigners moved to Constantinople within the 50-60 years following these events.

Imagine that you are a European merchant coming to an Islamic city. You come to the city, because you enjoy many economical privileges for trade. You are not as adventurous as Pierre Loti, so you don’t live in a Muslim neighbourhood. You still want a lifestyle similar to the one you had in your hometown. Where do you go? This is more or less the situation European merchants found themselves in during the 19th century. In Istanbul the one place where non-Muslims lived and drank alcohol was in Galata, the epicentre of non-Muslim life. However, Galata was not equipped to absorb all the new arrivals and needed to expand towards the open areas beyond its walls.

The fact that Levantines and non-Muslim minorities were financially in better shape than the rest of the population helped them construct majestic mansions in Pera while setting up their businesses, offices and bureaus in Galata. In doing so, they also brought many urban qualities and the lifestyle of Western Europe to Pera. That was the reason why Pera evolved as a European aristocratic settlement, while Galata remained a cosmopolitan area where the mood was more laid-back.

As European influence increased in the city, more Westernisation policies came into being. In 1857, Istanbul was divided into 14 municipal circles. The sixth circle, which consisted of Galata and Pera, was chosen as a pilot zone for European urban design. In 1858, the Sixth Municipal District Office, modelled after the Municipality of Paris, was established to operate from Beyoğlu. As per their 1860 plan, the walls of Galata were demolished to make commuting between Beyoğlu and Galata easier. Other projects prepared by the office included street cleaning, road widening, the repair, security and illumination of streets, the provision of public transportation, building maintenance, and the beautification of the area.

In June of 1870, Pera suffered one of its largest fire disasters. The fire killed hundreds of people, destroyed thousands of buildings from Taksim to Tarlabaşı, the Fish Bazaar, Galatasaray, Parmakkapı and a great part of Cihangir. The scale of the disaster created an opportunity to overhaul the design of the district. The Sixth Municipal District Office and its wealthy families played a key role in shaping Beyoğlu’s urban feel.

After the fire, Pera changed radically. Instead of wood, the main building materials came from stone and brick. A right to purchase property was given to foreigners in 1865 and this led the Levantenes to build a variety of buildings such as monumental structures, apartments, schools, sanctuaries, hotels, warehouses, and passages on the Grand Rue de Pera, today’s Istiklal Avenue. These buildings show a range of architectural styles from classical to Neo-Gothic, Neo-Ottoman to Art Nouveau. The famous shopping arcades such as the Halep Passage, the Hacapulo Passage (Hazzapulo), the El-Hamra Passage, and the Rumelian Passage are still present today. Istiklal’s most outstanding buildings, such as the Doğan Apartment Building, the St. Antuan Catholic Church, the Flower Passage, Narmanlı Han, the Pera Palace, the Egypt Apartment, the Swedish and French Palaces, the Botter Apartment, and Hagia Triada were all constructed during this period.

As the 19th century came to its end, Beyoğlu assumed the look of a European neighbourhood and became Istanbul’s center of finance, culture, and entertainment. It was easy to find posh cafes, stores selling luxury products from Europe, restaurants, and nightclubs that couldn’t be located anywhere else in the city. There were large and splendid theatres where famous European plays, operas, and concerts showed nightly. You could also find foreign enterprises such as foreign mail services, institutes, schools, and offices of professionals such as bankers, lawyers, doctors and pharmacies in the district. For the first time, Istanbulites got acquainted with “urban richness”, in the form of coiffures, beauty parlors, wigmaker shops, dry cleaner stores, bookstores, glassware shops, delicatessen shops and travel agencies. In short, Beyoglu was a Western neighbourhood in the middle of a Muslim city, where all languages of the world converged.

Beyoğlu retained its multicultural, multi-faith, and multi-national social structure for over a century. At one point, the population became more homegeneous due to certain social and political events, four of which stand out. First was the Wealth Tax (1942-43), which made non-Muslims pay an extraordinary tax on nearly everything. This was the first policy attempting to disadvantage the non-Muslims of Istanbul as a form of economic genocide.

The second important event was the founding of Israel in 1948. A Jewish population had always been present in Istanbul and was integral to Istanbul’s multicultural society. Soon, however, the vast majority of Turkish Jews immigrated to Israel for economic reasons, severely diminishing Istanbul’s Jewish population. In three years, between 1948 and 1951, Istanbul lost half of its Jewish population.

The third event killed Istanbul’s spirit, history, and whatever was left from Constantinople. The 6-7 September Istanbul Pogrom was a Turkish riot against Istanbul’s Greek community, meant to expunge them from the city. On the evening of September 5th, Istanbul received the news that a bomb attack had taken place in Atatürk’s birthplace in Thessaloniki. The Istanbul Express’s headline the following day read “Our father Atatürk’s house has been bombed”, inciting a riot which began with the attack on the Haylayf pasty shop in Pangaltı. The chaos then spread all over the city. The damage, both material and immaterial, was immeasurable. Following the events that September, many of the Greeks in Istanbul left their homes and businesses behind and emigrated from Turkey.

Next, the event that left Beyoğlu at its all-time low was the 1964 expulsion of the remaining Greeks in Istanbul. Due to the strained tensions between Greece and Turkey from the Cyprus problem, the Turkish government made the decision to expel nearly 40,000 Greeks from Istanbul on March 16th, 1964. This fateful decision proved to be a turning point in terms of Turkey’s homogenisation process. In addition to these four crucial historical events, the 1974 Cyprus Peace Operation, the ‘Citizen, Speak Turkish’ campaign, repeated military coups, a mass migration from Anatolia to Istanbul, and an unplanned urbanisation all contributed to the cultural devastation of Beyoğlu.

After the 1950s, the population of Beyoğlu decreased with the departure of non-Muslims. With the rapid industrialisation of the 1950s and 1960s, Istanbul became a magnet for migrant groups from rural areas of the country and Beyoğlu began to answer the need of cheap residences for rural people, who had been illegally occupying the buildings abandoned by non-Muslim residents. The district was gradually “Turkified”, which introduced some important changes to the social structure of the district. Beyoglu became home to numerous marginalised groups including sex workers, transvestites, Roma gypsies, Kurdishes, and many more. Brothels were opened and drug dealers took over the streets. Beyoglu became a hotbed of crime where people were afraid to walk on its streets even during broad daylight.

By the beginning of 1980s, Beyoğlu was completely run down. It was a hotbed of crime where people were afraid to walk on its streets even during broad daylight. It was no longer a Western neighborhood, nor a center of entertainment or culture. The arabesque culture began touching Beyoğlu’s spirit deeply. The cinemas, theaters, cafes, restaurants and bars had shut down one after another, and pavyons and gazinos began to take their place. During this era, Beyoğlu by night was strictly a male-dominated space!

Bedrettin Dalan, the first mayor of Greater Istanbul, took on the transformation of worn-out Istanbul to a global city. For him, Beyoğlu, was a place that needed rehabilitation from prostitution and drug trafficking, especially because it was one of the most prominent and historically dense part of the city. As a result, urban renewal projects were brought to the agenda with Beyoğlu as the focal point.

Various measures were taken to revive Beyoğlu, such as the establishment of the Association of Beautification and Preservation of Beyoğlu, the widening of Tarlabaşı Avenue and the pedestrianisation of Istiklal Avenue in 1990. In fervent pursuit of his goal, the mayor took on the liberty to demolish a large number of 19th century buildings and to relocate the thousands of people living in them. Thus the newly sanitised Beyoğlu became a haven for cafes, restaurants, hotels, cultural buildings, art galleries, bookstores, theatres, taverns and bars. Other activities and festivals have also played an effective role in the revitalisation process. Together, these essential developments then spilled over to the surroundings neighbourhoods such as Cihangir, Galata, Şişhane and Tophane, and a new impulse was given to the entire area.

Since the 1990s, the nostalgia could be experienced once again. Beyoğlu has regained its value and became the most favourable district in all of Istanbul. Beyoğlu is probably the only place that can be home to more than 15 million Istanbulities and it is not possible for tourists to skip Beyoğlu when they come to Istanbul. Presently, you can find a seedy side, with prostitutes and drug dealers, and a new cosmopolitan area that can be considered to be the centre of commerce, entertainment and culture as it was in its glory days. It is known that all aspects of culture and art in Istanbul originate from Beyoğlu, from the past to the present. It is teeming with cinemas, theatres, operas, art galleries, bookshops, festivals and biennial lovers; Beyoğlu is an important place to almost everyone. Today, Beyoğlu is the ambassador of Istanbul, embodying the city’s energy.

The Turkish Way of Proving Talent: Making Börek

It is 5am in Istanbul and the sun has just started to illuminate the street I am walking on. It is too early to find an open bakery in Kadıköy’s harbour and I’m too tired so there is no chance of me waiting for one to open. I’m dreaming of food but there doesn’t seem to be any opportunity of eating soon, which makes the world a bit of a darker place for me. . Still, I hope that something good can happen because it is Istanbul, the city where amazing things happen. Eventually, Istanbul doesn’t disappoint me. A food seller appears on the street and shouts something which I don’t understand as I don’t know Turkish at that moment. Yet, I see he carries something which is full of food. Now, there’re two possibilities; I go home and sleep with my empty stomach or I would try the food which this tiny Turkish man sells. As you can expect, I choose the second option and approach him full of excitement. What a great surprise that he sells something hot, sweet, and something without meat! Above all, a really big portion is only 4TL. What could be better for a hungry vegetarian! It was simply fabulous! What he was selling was “börek” and from then on it has been one of my favourite Turkish foods!

Continue reading “The Turkish Way of Proving Talent: Making Börek”